In the five years since the Mitchells announced to the world that they had solved the Rosslyn code, they've received modest recognition in the media and respectable sales of a professional recording of the work. They shrewdly timed their announcement of the solution to the release of the movie adaptation of The Da Vinci Code, giving reporters and producers a ready-made news peg. Over time, however, their story has faded to a curiosity. Interest in whether it is real has waned.

Stuart and Tommy Mitchell say they don't much care if people believe them. On my last day in Roslin, I met Stuart and his friend Ian Robertson at the chapel. Robertson and his co-author Mark Oxbrow wrote by far the best modern book on Rosslyn Chapel, Rosslyn and the Grail. Mostly, Robertson and Oxbrow debunk the various rumors and legends that have attached themselves to the chapel, including the crazy ones about the Holy Grail and Jesus' head. But when it comes to the Rosslyn Motet, they're more circumspect. "One 'code' that may actually exist within Rosslyn," Robertson and Oxbrow write, "is the mysterious carved cubes that ornament some of the arches in the chapel."

Robertson and Stuart Mitchell became friends after Rosslyn and the Grail went to press, but Robertson remains ambivalent about his buddy's theory. When we met at the chapel, the first thing Robertson asked me was whether I thought the code was real. I said I didn't know, but that it at least seemed plausible.

That's the maddening thing about the Rosslyn code. When you're standing under the cubes, watched over by the 13-piece angelic band, it all seems so obvious that you wonder why it took 500 years for someone to unearth the music. But when you go back to assemble the evidence, you realize that the Rosslyn Motet sits on top of a mountain of shaky assumptions. Is the resemblance between the cubes and Chladni patterns a coincidence? Could any random set of notes start sounding human-made when you hear them hundreds of times? Was it really feasible for these melodies to be produced in the 15th century.

Against these doubts, only the music stands as counter-evidence. The Rosslyn code's highest-profile critic is probably Warwick Edwards, a music professor at the University of Glasgow. Edwards, who attended the first public performance of the Rosslyn Motet in the chapel itself, judged that the final product didn't resemble any medieval music he'd ever heard. To that point, however, I don't believe you can judge the Mitchells' creation based on how medieval it sounds—this is more an issue of Stuart Mitchell's orchestration than it is with how the original melodies have been transcribed.

The code has several online doubters, the most prolific of which is the anonymous author of the blog "The BS Historian," who has written skeptically about the Mitchells nearly a dozen times in the past few years. The author's criticisms cover the gamut of the Mitchells' story, from the historical holes to the matching of Rosslyn's symbols to documented Chladni patterns. Others have parroted this skepticism. A commenter on the website of high-profile skeptic James Randi sums up a common reaction quite concisely: "I strongly suspect that this is yet another case of seeing what one wants to see, with heavy confirmation bias."

If the Mitchells' theory is indeed fabricated, it's still fascinating that they coaxed compelling, nonrandom-sounding melodies out of the Rosslyn Chapel's stone cubes. Whether any random series of notes can sound beautiful in the hands of an expert arranger is a tough question to answer, though one footnote to the Rosslyn story tilts me a bit towards the Mitchells' side.

On my first morning at the chapel, before I'd met Stuart, a tour guide named Roger told me he'd heard that many of the cubes had fallen from the ceiling over the years. A stonemason, Roger believed, had replaced them on the ceiling at random as part of a restoration a few decades prior. Uh oh, I thought—I've crossed the Atlantic to investigate a centuries-old song that's younger than I am.

As it turns out, the stonemason, an elderly man name Joe Lang, still lives a few miles from the chapel. Lang later told me the real story: Just a few of the cubes at the chapel's northern end had fallen—"no more than seven or eight" out of 213. But I didn't know this when I talked to Stuart over dinner that first night. "I absolutely hate the end of the music, because it's the only part that doesn't make any sense," he told me. If, in fact, the last few cubes are out of place, this might explain why.

![]()

After three days in Roslin, I still wasn't totally convinced by the Mitchells' story. In search of more evidence, I paid a visit to the Scottish National Library in Edinburgh. I wanted to see the manuscript on chivalry and warfare that William St. Clair, the chapel's founder, commissioned from Sir Gilbert Hay—the man Tommy and Stuart Mitchell believe might be responsible for Rosslyn Chapel's carvings. The Hay manuscript is well guarded. To see one of Scotland's most-treasured artifacts, you have to get two senior curators to sign off on the request; at that point, the manuscript must be delivered from a separate location.

Hay's 500-year-old words are penned in the elegant handwriting of a professional scribe, and are more or less impossible for a lay reader to decipher. In many places, the book has been idly vandalized. The Curroy family, later owners of the manuscript, took the liberty of doodling in the margins, practicing their signatures and drawing little hands with pointing fingers.

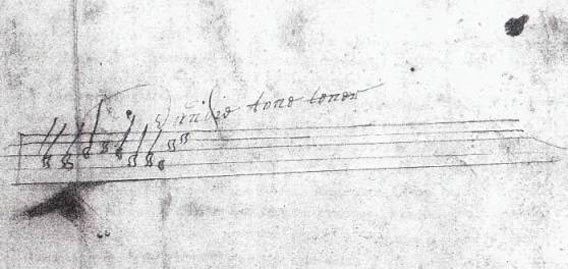

The very first page in the tome is a half-size sheet with some incomprehensible script on the front. When I turned it over, however, I saw something flabbergasting: a nine-note melody sketched out on a familiar five-line staff.

Was this incredible proof that Stuart and Tommy Mitchell had been right all along? I compared these nine notes to the score of the Rosslyn Motet, however, and I didn't turn up a match. I sent the image to Stuart, and he pointed out that there was a link—the notes in the manuscript pass through the same scale as most of the melodies he decoded. It's not a strong connection, but it's something.

Alas, Oxford University's Sally Mapstone—who wrote her dissertation on Hay's work—told me this was all wishful thinking. The manuscript in the Scottish National Library did not belong to Sir Gilbert Hay; it was copied about 40 years later for a St. Clair descendant. Mapstone identified the script above the music as 18th-century. Unless another detective found himself on the same trail, it's probably just a tantalizing coincidence.

![]()

More than 500 years after the Rosslyn Chapel was built, codes continue to fascinate and confound us. Back in November, the New York Times ran a profile of Jim Sanborn, the artist responsible for one of the most famous unsolved codes of modern times. It is called "Kryptos," and it lives on a copper sculpture at CIA headquarters in Langley, Va. The serpentine installation contains a long series of letters broken into four parts, with each section encrypted using a different method. The first three sections have been solved, but the fourth has proved to be so confounding that Sanborn felt compelled to give the Times a six-letter clue in the hope that it would hurry along the process. He's sick of dealing with it.

Kryptos consists of four different substitution codes, in which each letter represents one letter in the solution. One of the four remains unsolved.

When I got back from Scotland, I showed Sanborn some images of the cubes. He seemed to think they might be the work of a cryptographer. The trouble with the chapel's cipher, he said, was that the act of solving it doesn't prove it was a cipher in the first place. It's virtually impossible to crack the fourth part of Kryptos and get the wrong answer—the odds that the same code could produce two different coherent passages of text is functionally zero. (This hasn't prevented people from confronting Sanborn with outlandish solutions, sometimes on his lawn.) While Sanborn told me that Kryptos has meaning beyond the passages, he verified that—unlike the alleged Rosslyn Code—you don't need any information outside the letters themselves to crack it.

Since there are only 12 unique symbols, it's unlikely someone else will find a written message in the Rosslyn cubes. Anything is possible, but I think the book on the stone cubes is closed. Either the Rosslyn Motet is a 500-year-old musical message, or the cubes mean nothing.

But perhaps that's not the point. The chapel's designer, I'm sure, would be pleased to know that we're still engaged by his creation—pondering what it means and what he wanted us to see. By happy coincidence, I had just finished reading an exquisite little novel by the British author J. L. Carr, A Month in the Country. The narrator, a World War I veteran, is a restorer of medieval paintings that had been whitewashed over by a disapproving churchman. This line of work takes him to a tiny settlement in northern England, where he slowly chips away at a canvas. As he persists, the original artwork—a masterful depiction of the Judgment—comes into focus:

Here I was, face to face with a nameless painter reaching from the dark to show me what he could do, saying to me as clear as words, "If any part of me survives from time's corruption, let it be this. For this was the sort of man I was." ( slate.com )

No comments:

Post a Comment